Thailand Legalized Weed. So Why is it Handing it Back to Crime Bosses?

Thailand build a thriving, if chaotic, legal marijuana market in just three years. Now, ti's undoing it all. And old smuggling mechanisms are rapidly roaring back to life.

Nine became eight. In 2022, Thailand became the first Asian country to legalize recreational cannabis. Last week, it became the first country in the world to reverse that decision. Cannabis is now fully legal in just eight countries: Canada, Georgia, Germany, Malta, Mexico, South Africa, Uruguay, and parts of the U.S. and Australia.

For Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin’s government, the U-turn was overdue. He’s slammed the 2022 rollout as reckless:

No real oversight of the thousands of dispensaries that opened overnight

A spike in youth use

And a national image sliding toward drug-tourism free-for-all

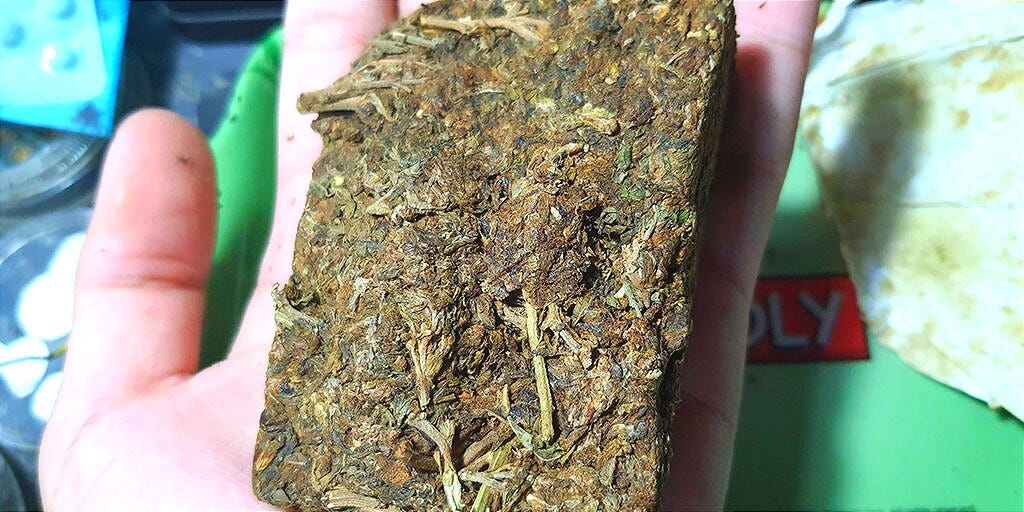

To be fair, the criticisms weren’t wrong. There was no Cannabis Act. Local authorities made up their own rules. Age checks were patchy, product regulation nonexistent. Dispensaries were supposed to sell only low-THC cannabis—yet shops were full of high-potency buds or illegally imported Lao “bricks.”

Still, was the right fix to slam the door on everything?

Before Legalization: Crime Ran the Market

For decades, Thai cannabis was part of a state-tolerated narco economy. In the '70s and '80s, “Thai Stick,” potent, often opium-laced, bound to bamboo skewers, was a global brand. Smuggling rings, backed by Thai-Chinese syndicates and military protection, moved it across the Pacific via Golden Triangle heroin routes. Ports like Trat and Chanthaburi were key hubs. Police, army, and customs officers took their cut.

By the 2000s, cultivation had shifted to Laos and Myanmar. The product became cheaper and dirtier: compressed bricks of low-quality cannabis, pumped with pesticides and trafficked by the ton into Thailand. Tourists and locals bought it. Cops shook people down for carrying it. Everyone got paid.

Then came 2022.

Legalization crashed the black market. Dispensaries sold cleaner, stronger weed. Licensed growers pushed out illicit ones. Mekong smugglers lost buyers. Police couldn’t extort people for a gram in their pocket. For a brief moment, the old ecosystem choked.

But organized crime adapted. Syndicates laundered profits through legal storefronts. Imported high-THC strains from Canada and the UK showed up on menus. And Thai-grown weed started quietly flooding into overseas black markets.

Now, with recriminalization, organized crime groups will feast on a thriving industry suddenly cast adrift, with thousands potentially losing their jobs.

Here’s some ways how.

Return of the Brick Weed Barons

For decades before 2022, Thailand’s marijuana market was dominated by cheap, compacted “brick” cannabis smuggled from Laos and Myanmar. These kilo-weight bricks of low-grade, outdoor-grown weed were easy to move and sold at rock-bottom prices. Legalization hit this illicit trade briefly, as Thai consumers and tourists turned to higher-quality flower in legal shops.

But seizures have continued since legalization. In late 2022, for example, authorities in Nakhon Phanom seized around a ton of Lao-grown cannabis – part of an estimated 8–10 tons seized in that province that year. And in February 2023, a Mekong riverine unit in Nakhon Phanom caught 580 kilograms of compressed cannabis in an abandoned pickup, confirming smugglers were still active.

With legal dispensaries now shut or pushed into medical-only sales, demand for cheap illicit weed may rebound. Many poorer Thais, or anyone who can’t afford boutique buds, will again turn to bricks despite the poorer quality. It may take a while.

With licensed dispensaries now being forced to close or pivot to medical-only sales, demand for cheap illicit weed is poised to rebound. Many poorer Thai consumers – and any tourists who can no longer buy pricey boutique buds over the counter – will turn back to the black-market brick, quality be damned. It may not happen overnight (habits changed over the past three years, and some users will try growing their own), but the economic pull of cut-rate cannabis is strong. Laos’s weed syndicates, which had begun redirecting shipments to other markets (like Malaysia) during Thailand’s legal stint, now have every incentive to refocus on Thailand. The profit margins are simply too good to ignore, especially with far less competition from legal Thai growers.

Crucially, the cross-border smuggling infrastructure that long supplied Thailand’s market is still in place. The Mekong boat landings, the rural couriers, the network of bribes to police and border guards – these didn’t disappear in 2022. Traffickers will dust them off and scale up deliveries as Thai customers trickle back.

Worse, Thailand’s criminalization of weed may torpedo Laos’ nascent attempts to legalize its own industry.

Police Shakedowns and Bribes Comeback

Legalization partilally disrupted a common racket for Thai law enforcement: extortion. Before mid-2022, if you were caught with even a few grams of cannabis, this often meant into on-the-spot bribes. Tourists and locals alike have long reported that some Thai police would demand “fines” in cash to avoid charging someone for a joint or failing a urine test.

Decriminalization put a stop to all that. After 2022, while some dispensary owners may have paid “inspection fees” to local officials in order to operate without harassment, extortion became harder to accomplish.

Now, with cannabis being re-listed as a controlled narcotic, street enforcement regains its teeth – and its value. Every person caught with a joint or a few grams is once again a potential walking payday for unscrupulous officers. Police could even detain, intimidate, or arrest users and low-level dealers, then offer to make the charges disappear in exchange for cash under the table. In short, the corrupt links between traffickers and law enforcement may snap back into place.

Beyond graft, a return to harsher enforcement raises the specter of rights abuses. Thailand’s history here is grim. The 2003 “War on Drugs” under then-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra led to about 2,800 extrajudicial killings in just three months, including many innocent people unconnected to drugs. Should the government now double down on a hard-line stance, such as fueling a moral panic about youth cannabis use, we could see a return of aggressive raids and intimidation. Activists are worried about violent crackdowns and planted evidence making a return.

Surplus Supply Fuels Export Boom

Evidence of a burgeoning export black market emerged even while cannabis was legal in Thailand. Throughout 2023 and early 2024, authorities in Europe and Asia noticed a spike in Thai-sourced marijuana turning up in places it shouldn’t. In the U.K., border officials were overwhelmed by a wave of packages and suitcases coming from Thailand. In fact, in late 2024, the UK’s Border Force detected over 15 tons of cannabis mailed from Thailand in just one quarter. And in February 2025, a joint operation at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport seized over two tons of cannabis from outgoing air passengers in a single sweep. Many couriers were amateur “mules”, including Western tourists, lured by free trips or quick cash to smuggle weed in luggage.

With legal outlets now closing, the incentive to send Thai cannabis abroad will only increase. Thai cannabis is cheap at the source, and in markets where cannabis remains prohibited, the street value is many times higher. For example, British authorities estimated the 2-ton airport haul at about £6 million, roughly £3,000 per kilo, based on UK black-market prices. That’s easily 4–5 times what the same amount might fetch from a Thai farm. Likewise, in East Asian countries like South Korea or Japan, where marijuana penalties are severe, a kilo of top-shelf bud can command astronomical prices.

In effect, Thailand’s reversal may turn it into a major exporting hub for illicit cannabis, the mirror image of its earlier goal to be a regional medical marijuana hub. During 2022–24, much of the cannabis grown by Thai farmers was consumed domestically through legal channels. Now, that same supply, especially high-THC indoor crop that can’t be sold under new medical-only rules) will be diverted to the black market, likely for export. The big winners are transnational trafficking networks, who will gladly redistribute Thai product abroad for a premium.

Dispensaries and Growers Go Underground

By mid-2025, Thailand had around 11,000 licensed cannabis dispensaries operating across the country, plus numerous other unlicensed outlets and pop-ups. These businesses ranged from boutique Bangkok stores catering to tourists, to mom-and-pop shops in small towns, to farmers’ co-ops selling homegrown herb. With the legal market now being dismantled, what will all these players do?

Many will reluctantly shut their doors, others will seek to fully comply with the new regulations, but not all.

The sunk costs are high: entrepreneurs have poured millions of baht into inventory, storefronts, staff, and marketing. There’s also stock on hand that can’t simply be erased. The result is that a significant segment of the former legal industry will pivot to the grey or black market rather than vanish. This creates an opportunity for organized crime to step in as partner, supplier, or financier.

One likely outcome is the rise of pseudo-legal “clinic” fronts. Dispensary owners desperate to stay afloat are already exploring re-registering as medical clinics or wellness centers, since the new rules allow cannabis sales with a doctor’s prescription. In practice, this might mean hiring (or paying off) a doctor to sit in-house and write pro-forma cannabis prescriptions for virtually any customer willing to pay a fee. As one cannabis activist quipped, it could become a pay-to-play loophole – anyone with cash can get a medical note and buy weed, recreating a de facto recreational market behind a thin medical veneer.

Regulators will undoubtedly try to crack down on blatant abuses, but historically in Thailand, where there’s demand, such “prescription mills” can thrive (consider the parallel of how some Thai pharmacies quietly sell prescription opioids or amphetamines under-the-counter despite strict laws). Keeping such operations running will depend on quiet collusion: paying bribes to inspectors to look the other way, falsifying records, and sourcing product outside official channels when supply runs short.

Other dispensaries will go fully underground. Expect delivery services operating via encrypted apps or private Line groups. During the legal era, some unlicensed shops already functioned this way to avoid scrutiny. This could become the norm.

These covert businesses will likely turn to the only supply chain available: the illicit one. Domestic growers who were licensed may keep cultivating high-THC strains but will have to sell them illegally, perhaps through brokers connected to gangs. Former dispensaries might strike deals with traffickers smuggling in cheaper Lao or Cambodian weed to resell. In effect, the distribution network that briefly operated in the open will be driven into partnership with traditional narcotics networks.

Many small-scale Thai cultivators, who enjoyed a brief period of legitimacy – will now face a stark choice: cease growing or sell on the black market.

There is evidence that even during legalization, organized crime elements had their eyes on the industry, including for money laundering. Investors rs now have a choice: pull out, or help their Thai ventures go illicit. Some will choose the latter, injecting black-market capital to keep shops running under the radar.

The fallout is a lose-lose for law-abiding entrepreneurs and consumers. Reputable small growers unable to pivot will go bankrupt, while the more desperate or daring will team up with criminal backers. As cannabis activist Chokwan Chopaka told Time Magazine: Businesses won’t disappear so much as “go underground,” and the trade will be “managed by the corrupt underground system” once again.

Same old news https://open.substack.com/pub/woochi143/p/sweet-tea-and-truths-marijuana-monopoly?r=5xgb18&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false