How Organised Crime Handed Chile's Election to the Far Right

Chile's president-elect, José Antonio Kast, skillfully capitalised on a middle-class panic about criminal gangs, a resurgent Tren de Aragua, and continued attacks by Mapuche groups in the south.

José Antonio Kast has won a landslide victory to become Chile’s next president. The far-right candidate built his campaign around a major promise: to reclaim a nation he argued had been surrendered to foreign criminal organizations, drug traffickers, and the chaos of uncontrolled borders.

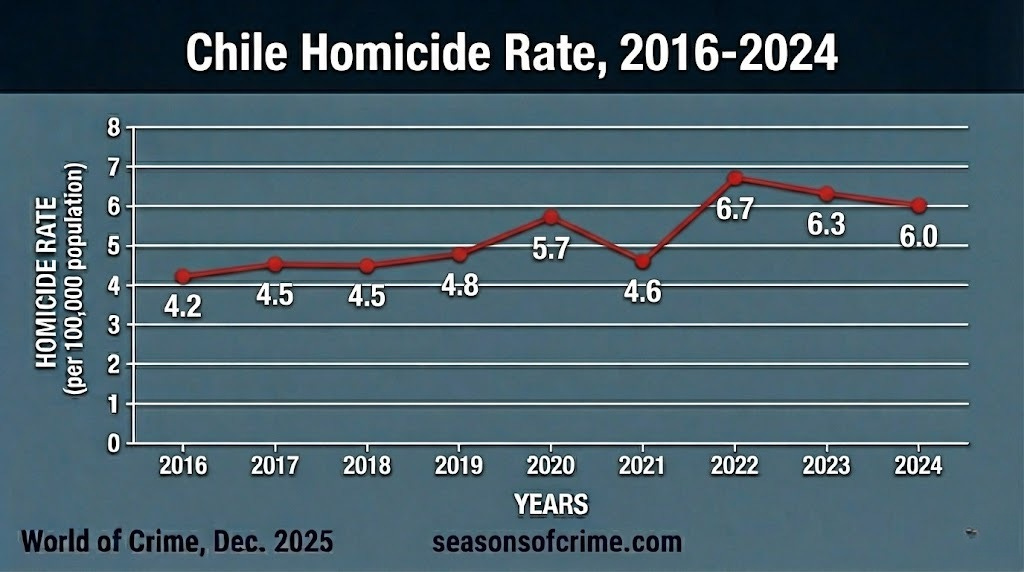

The numbers certainly tell a stark story. Between 2012 and 2022, Chile’s homicide rate exploded by 572%, climbing from 2.6 to 6.7 per 100,000 inhabitants. The outgoing administration of President Gabriel Boric did manage to stabilize that figure through 2024 and 2025.

But despite this, violent crime in Chile has changed. Kidnappings reached a record 868 cases in 2024, up from 360 a decade prior. In June 2025, armed men abducted Gonzalo Montoya, the mayor of Macul, from his home. The perpetrators were identified as members of Tren de Aragua, the Venezuelan transnational criminal organisation that has a heavy role in human trafficking, extortion, and drug sales across northern Chile and in Santiago.

Kast weaponised these incidents throughout his campaign. He promised a reinforced physical barrier along the northern border, mass deportations of irregular migrants, a maximum-security mega-prison modeled on El Salvador’s CECOT, and military deployment to “reconquer” neighborhoods he claimed had been abandoned to criminal control. His campaign painted the violence, dismemberments, torture killings, and contract killings as fundamentally alien to Chilean society, imported from Venezuela and Colombia. And it worked.

Now, World of Crime takes its readers through Kast’s claims, the Chilean reality, and how Chileans came to perceive organised crime as an existential threat to their nation.

Takeaway 1: How Violence Changed in Chile

The government may have stabilised the homicide rate, but failed to curb more spectacular forms of violence. The shift from street brawls to organised executions created a terror gap that statistics could not bridge.

Gabriel Boric’s administration entered the 2025 election cycle with what it considered a significant security achievement. The “Streets Without Violence” plan, launched in response to the 2022 homicide peak, had managed to stabilize the killing rate at through increased police coordination and targeted interventions in high-violence municipalities.

But the stabilisation masked a shift that government data failed to capture. The violence had become more professional. By 2024, contract killings accounted for over half of homicides, according to police data.

Then came a number of specific incidents that defined the campaign. In February 2024, the body of Venezuelan dissident Ronald Ojeda was discovered in a suitcase, encased in cement, after being kidnapped from his Santiago apartment by men posing as police. Investigations linked the murder to Tren de Aragua, allegedly operating on order from contacts in the Venezuelan government. In Maipú and Arica, more bodies were found in similar states, dismembered, tortured, and displayed. This type of crime was unheard of in Chile until recently.

Kast built his campaign argument around this. In speeches across Santiago’s suburbs, he dismissed the government’s homicide statistics as “managing spreadsheets while citizens are being hunted.” For Kast, even though fewer people were dying, more Chileans were living in fear. The message worked.

Takeaway 2: Tren de Aragua and Beyond

Organised crime in Chile has become a fragmented patchwork of sophisticated criminal enterprises, with Tren de Aragua as the most visible but far from the only player.

When Chilean law enforcement conducted coordinated raids to take down Tren de Aragua’s Los Gallegos cell in mid-2024, investigators discovered treasury ledgers, defined organizational hierarchies, and operational manuals. The cell had acquired legitimate inter-regional bus companies operating between Tarapacá and Coquimbo, moving undocumented migrants south and drugs north through legal business infrastructure, according to police intelligence reports.

The dismantling of Los Gallegos was celebrated as a major victory. Dozens of operatives were prosecuted, the leadership structure was destroyed, and the northern smuggling corridor was disrupted. President Boric’s administration presented it as proof that coordinated law enforcement could defeat even transnational organizations.

But the victory was temporary. Within months, Los Mapaches emerged in Santiago. They emerged not as a direct continuation of Los Gallegos but as a separate TdA-affiliated cell. Los Mapaches moved quickly. By June 2025, they had established extortion networks in migrant communities, prostitution operations in Estación Central, and the capacity for high-profile operations like the Montoya kidnapping.

This speedy rise proved how TdA’s franchise system, with local cells operating with significant autonomy, has created a hydra that is difficult to defeat.

And TdA is only one element of Chile’s organised crime landscape. The retail drug market in Santiago is controlled by a patchwork of local Chilean gangs, who have clashed violently for key neighborhoods.

Chile is suffering the consequences of a Latin American problem. With no hegemonic organisation imposing order, violence is surging between multiple groups.

Kast exploited this complexity to simplify the narrative. While TdA became his campaign’s primary villain, he successfully conflated all organised crime under the umbrella of “invasion” and “narco-terrorism.” His proposed CECOT-style mega-prison was for all “high-risk” criminals. The government pointed to nuanced intelligence operations targeting specific groups differently. Kast promised blanket militarisation.

Takeaway 3: The Mapuche November Surprise

The long-running conflict with the Indigenous Mapuche in southern Chile retained a capacity for strategic violence that could derail a national narrative in a single week.

Chile’s security crisis is not limited to transnational gangs and urban violence. In the southern regions of Araucanía and Biobío, the country faces a fundamentally different threat: a decades-old territorial conflict between the Chilean state and radical Mapuche groups demanding the return of ancestral lands seized during 19th-century colonisation and subsequently granted to forestry corporations and agricultural enterprises.

The violence has escalated dramatically since the 2010s. Organised cells like the Weichan Auka Mapu (WAM) have conducted systematic arson campaigns targeting what they viewed as symbols of territorial occupation. Between 2020 and 2024, hundreds of attacks destroyed logging trucks on the Pan-American Highway, burned schools and churches in rural communities, and targeted the machinery and facilities of forestry giants operating on disputed lands. The conflict turned lethal in April 2024 when three gendarmes were ambushed and killed.

However, the Boric administration believed it had contained this front with a longstanding military deployment. Violence in the south had dropped by 53% in early 2025 compared to 2024, and by 77% compared to 2021, according to Interior Ministry statistics.

Then came November 2025. Following the sentencing of WAM members for previous attacks, the group launched eleven coordinated arson operations in a single week, shortly before the December 14 election. Logging trucks were set ablaze in broad daylight on the Pan-American Highway. Agricultural machinery worth millions was destroyed in nighttime raids on farms. Images of this violence dominated news cycles for days, erasing any impact from the ten months of statistical decline.

Kast seized the moment. To him, the Mapuche perpetrators were narco-terrorists, vowing that he would end all dialogue with such groups and prosecute their leaders.

Takeaway 4: The Paranoia Gap

For the middle class, security was not measured only by homicide rates but by the perceived loss of daily freedoms and frequent news about closed schools, early curfews, and extortion payments.

While Kast’s campaign emphasized spectacular violence and foreign gangs, his electoral breakthrough in Santiago’s middle-class suburbs came from something more intimate: the accumulation of small surrenders that reshaped everyday life. It wasn’t just that Chilean voters were afraid of being murdered, the country’s homicide rates remain far, far below most of its neighbours.

Instead, they were exhausted by a narrative that constantly highlighted the spread of crime.

Curiously, narco-funerals became an example of this. In May 2025, the Boric government passedemergency legislation restricting high-risk funerals to 24-hour windows and prohibiting certain displays after a gang member’s burial in Pedro Aguirre Cerda featured gunfire, blocked streets, and forced two schools to suspend classes for the day. Similar incidents in Valparaíso had seen parents rushing to retrieve children as funeral processions turned violent.

The law was intended to solve a problem, but its very necessity became the story. The fact that the state needed to regulate when and how criminals could be buried signaled to some voters that organised crime was dictating the terms of civic life.

The extortion economy spread beyond traditional criminal territories into middle-class commercial zones. The “vacuna” model, gangs demanding protection payments from small businesses, has arrived in downtown Santiago, affecting bakeries, barber shops, restaurants, and corner stores. Unlike drug trafficking, extortion was visible on the streets middle-class Chileans walked daily.

In campaign stops in traditionally center-left middle class areas, Kast framed the election as a choice between freedom and captivity. He vowed to expand self-defense rights for citizens who fought back against attackers and proposed lowering the age of criminal responsibility to prosecute juvenile offenders.

For exhausted suburban voters, government statistics provided cold comfort. Kast provided recognition.